I’ve been interested in ambient data displays for a while. They’re pretty common in modern life: arrival/departure boards for transit or flights, traffic condition signs (“X minutes to Y” on a highway), the current floor display for an elevator, open/closed signs for businesses. Clocks are probably the oldest kind, going back to early timekeeping with sundials.

My house is near-enough to an airport that I can see and hear airplanes during the day (especially while working from home). Earlier in the year I bought a software-defined radio receiver and set it up to receive ADS-B data. But I didn’t want to have to have a browser open all day to look at the map; I wanted an easier way to identify what airplane I heard.

I was looking at dot-matrix LED displays for a while, the kind that is used for signage. But I never found one that seemed both easy to use (i.e., didn’t require me to build my own electronics; I am not much of a hardware person) and was inexpensive. I then saw a YouTube video about cash registers and learned that pole-mounted customer displays are typically USB. I can do USB…

So I bought one. Looking on eBay I found a few used ones that were in the $20 to $30 range. I ultimately ended up with an LD220-HP (or HP LD220).

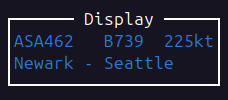

Here it is in all its glory:

Driving the display

Making the display actually display something interesting meant writing some software. Fortunately the display is attached as a USB serial adapter, and when it powers on its self-test shows the settings to connect: 9600 baud, 8 data bits, no parity, and one stop bit; this is a very common serial setting. While the display I purchased did not come with any documentation, I was able to find out through some Internet searches that it supports a few command sets including EPSON (or ESC/POS) which seems common. I eventually found a manual and the commands in it seemed to work for the display.

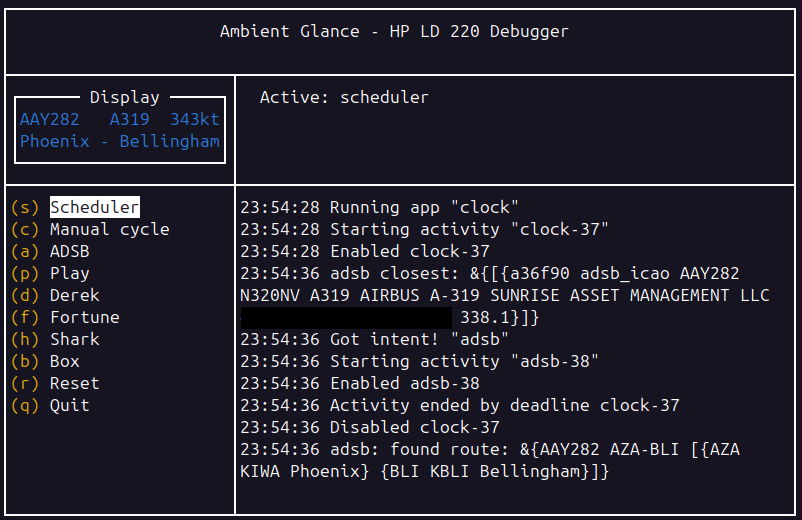

I typically write software in Go, and this was no exception. I found a serial library that seems to work really well, and I started writing my own library to handle the display. I also knew that I wanted to have a little UI I could run locally that would mirror the display; this would let me debug more effectively (i.e., ensure I understood well how the display processed commands) and give me control over how I wanted to provide data to display. I landed on tcell to handle a terminal UI (TUI). It also has the nice benefit of letting me separate a development environment (like my laptop) from where I would eventually use the display, especially since I wanted the display to run all the time even when my laptop is off.

So I built an interface to handle writing to the display, with a few methods that let me control position and clearing behavior:

type Display interface {

io.WriteCloser

Reset() error

Clear() error

MoveCursor(CursorPosition) error

MoveCursorCR(byte, byte) error

ClearLine() error

}

type CursorPosition int

const (

CursorUnchanged CursorPosition = iota

CursorTopLeft

CursorBottomLeft

CursorRight

CursorLeft

CursorUp

CursorDown

)I implemented this interface four times:

- A driver using the serial library for the physical display

- A driver using tcell for the TUI

- A chain so I could write to both the physical display and TUI at the same time

- A “locking” implementation (more on that later)

Scheduling “apps”

The primary thing I wanted to use the display for was ADS-B data, but there aren’t constantly planes flying over my house. So I also wanted other things to show. My idea was to have effectively a carousel that switched between different ambient data sources and could be interrupted any time a plane was detected close enough. I ended up deciding on modeling this as “apps” with a basic preemptive scheduler, “activities” modeling an active app that was driving the display, and “intents” for apps that wanted to interrupt the currently-active activity. (I haven’t really done much Android programming, but I stole the names from there.)

Right now I only have 3 apps:

- Clock

- Fortune (it just runs the

fortune(6)program and shows it) - ADS-B (more on this below)

The apps each fulfill an interface like this:

type App interface {

Name() string

Activate(id string) (Activity, error)

Stop(id string) error

}

type Activity interface {

Run(ctx context.Context, d display.Display) error

}The scheduler cycles through the apps, invokes app.Activate to get an

Activity, then calls activity.Run passing it a context.Context and

the Display interface. The context is used for cancellation so the activity

knows when it is no longer active, but that’s more of a nicety than a

requirement; the actual Display that is passed in is the locking

implementation I mentioned earlier. This locking implementation can be

controlled to know when it is enabled or disabled; the scheduler enables only

one lockable display at a time and disables it when the activity is preempted

(or if it exits on its own). This way the scheduler can be sure that there is

only one activity able to access the display at a time, even though the

activity runs in its own goroutine and the scheduler can’t forcibly kill it.

The main scheduler loop runs a set of apps with a 3 minute timer and then

switches to the next. But it also listens for an Intent.

type Intent struct {

Name string

Activity Activity

}Apps can generate Intents if they have something important to display. Any

intent that is received interrupts the regularly cycling apps and the provided

Activity can run until it exits (it won’t get canceled by the scheduler). As

of now I only have one intent-generating app, so I have not implemented

preemption of intent-delivered activities yet.

Debugging

I’ve described what I think is a reasonably complex system. Because I have a

TUI mirror of the physical display, I also wanted both a UI that I could use to

manually control aspects of it (like start and stop the ADS-B app, manually run

different display programs, etc) and give me log output (a normal logger to

standard out would interfere with the TUI). tcell gave me a reasonable

structure to divide the terminal into a few different areas and some primitives

that handle input and output. I ended up only using two different kinds of

primitives: 3 TextViews and a List. You’ve already seen one of the

TextViews; that’s the mirror of the physical display. A second one is used

to report status of what’s running (though mostly that just says “Scheduler”

now) and a third one is used for logs. The list is interactive and lets me

toggle behaviors.

Getting logs working was important for me since I tend to rely on a lot of

printf-style debugging when I write code. The log view was neat to get

working; a TextView implements io.Writer but needs to be controlled for

when it redraws and how it should behave when there is overflow (wrapping and

scrolling). But once I configured it I was able to hook it up to the standard

log package and that was enough for my needs.

logView := tview.NewTextView()

logView.SetTextAlign(tview.AlignLeft)

logView.SetBorder(false)

logView.SetWordWrap(true)

logView.ScrollToEnd()

logView.SetChangedFunc(func() {

app.Draw()

})

l := log.New(logView, "", log.Ltime)Put everything together and it looks like this:

ADS-B

I glossed over this a little earlier, but I built an ADS-B receiver for myself earlier in the year. I mostly followed a few different guides, one of which recommended this Nooelec USB RTL-SDR as a basic radio receiver. The SDR Enthusiasts guide helped me get started with the software side and I am using their containers (though I have a few slight modifications that I keep meaning to send upstream and haven’t yet). The main software components are readsb to decode the signals, tar1090 for a local map UI and API, and feeders for FlightAware, FlightRadar24, and adsb.lol. FlightAware and FlightRadar24 both grant free premium plans to feeders, which lets me look up more details about flights and aircraft. adsb.lol is a community project but offers a nice API for route information.

My ADS-B app reads from my tar1090 instance for finding the closest aircraft within a small radius, then retrieves route information from adsb.lol. It then formats all of this for output on the display.

Conclusion

This was a pretty fun project for me. It’s mostly over now, though I might add another app displaying OneBusAway transit information. It was a great learning experience, and I’m super happy when I hear an airplane, look at the display, and know what I’m hearing. I’ve posted the code to GitHub and am certainly glad if it’s of use to anyone else.

Additional references

- LD220 manual

- SDR Enthusiasts ADS-B guide

- pyserialpos - I didn’t find this until I was literally writing this blog post, but the code illustrated how to send custom bitmaps to the display which I hadn’t figured out yet.

Comments via 🦋

Join the conversation